Tracking your habit streaks with advanced queries in logseq

Tracking your habit streaks with advanced queries in logseq

In this tutorial, I will walk you through an advanced query in logseq that keeps track of your habit streaks. This tutorial is mainly intended for educational purposes as there are many more (and potentially more efficient) ways to track your habits within logseq. We will cover the basic syntax for advanced queries, including the :inputs and :rules clauses, as well as definitions of recursive rules and producing a table view with HTML hiccups. Furthermore, we will cover a way to count occurences based on conditions. Logseq uses datalog (more specifically datascript) for the queries. If you have not yet read the learndatalogtoday tutorial, I highly encourage you to do it now.

The habits block

The idea behind our query is based on this blog post: the tracking itself happens in the journal days in a specific block with the property type being set to tracker. This blog will contain one property for each habbit that you want to track. In the example below, we track the daily sport activities and our Anki usage. Furthermore, we will have one more property in this block, backlink. This property is a link to the journal entry of the previous day and it will come in handy later. As of the writing on 2023-08-28, I have done my daily round of Anki, but I haven’t been out for sports yet. Therefore, my habits block on the daily journal page looks like this:

![]()

To automate the creation of the habit block and especially the backlink, I have added the following block to my daily journal template. By default the hobbies are set to false.

type:: tracker

anki:: false

sports:: false

backlink:: <% yesterday %>

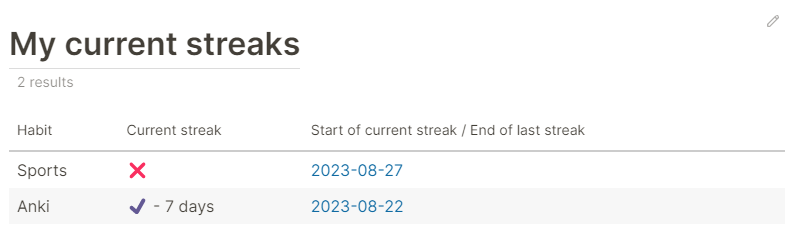

Next, let’s take a look at what my habit streaks for this day look like.

My tracker shows that I am on a 7 days streak with Anki that started on 2023-08-22. Furthermore, it shows me that the last time I made some sports was yesterday, as can also be seen by this entry for 2023-08-27.

![]()

The advanced query

The above table is created by this advanced query:

{

:title [:h1 "My current streaks"]

:query

[

:find (count ?p) (sum ?habit-today) ?habit-name (min ?date)

:keys count today habit lastdate

:in $ ?today [?habit ...] [[?habit2 ?habit-name]] %

:where

[(= ?habit ?habit2)]

[?p_today :block/journal-day ?today]

[?p_today :block/journal? true]

(or-join [?p ?p_today ?habit ?habit-today ?date]

(and

(pages-next-day ?p ?p_today ?habit true ?date)

[(ground true) ?habit-today]

)

(and

(pages-next-day ?p ?p_today ?habit false _)

[(ground false) ?habit-today]

[?p :block/journal-day ?date_]

[?p :block/original-name ?name]

[(vector ?date_ ?name) ?date]

)

)

]

:inputs [:today [:anki :sports] [[:anki "Anki"] [:sports "Sports"]] ]

:rules [

;; similar to predefined property rule

[(test-property ?b ?type ?testval)

[?b :block/properties ?props]

[(get ?props ?type) ?val]

[(== ?val ?testval)]

]

;; check whether specific habit was done in tracker block

[(habit-block ?b ?habit ?val)

[test-property ?b :type "tracker"]

[test-property ?b ?habit ?val]

]

[(pages-next-day ?p1 ?p2 ?habit ?val ?date)

;; fastest when we begin search at the known page ?p2

[?b2 :block/page ?p2]

(habit-block ?b2 ?habit ?val)

[?b2 :block/refs ?p1]

[?p1 :block/journal? true]

[?p2 :block/journal-day ?date2]

[?p2 :block/original-name ?name2]

[(vector ?date2 ?name2) ?date]

]

[(pages-next-day ?p1 ?p2 ?habit ?val ?date)

;; fastest when we begin search at the known page ?p2

[?b2 :block/page ?p2]

(habit-block ?b2 ?habit ?val)

;; ?px is the page that ?p2 links to.

;; Is it connected to ?p1? If yes, then ?p1 and ?p2 are also connected.

[?b2 :block/refs ?px]

[?px :block/journal? true]

(pages-next-day ?p1 ?px ?habit ?val ?date)

]

]

:view (fn [rows] [:table

[:thead

[:tr

[:th "Habit"]

[:th "Current streak"]

[:th "Start of current streak / End of last streak"]]]

[:tbody

(for [ r rows] [:tr

[:td (get r :habit)]

[:td (if (> (int (get r :today)) 0)

(+ "✔️ - " (get r :count) (if (> (int (get r :count)) 1) " days" " day"))

"❌")

]

[:td

[:a

{:href

(str "#/page/" (nth (get r :lastdate) 1))

} (nth (get r :lastdate) 1)

]

]

])

]

])

}

Structure of the query

The above query is entirely enclosed by curly brackets. It is coarsely structured by keywords that we will briefly discuss. You can use hiccup within the :title to quickly explain your query. Next comes the datascript :query enclosed by square brackets. It describes which information the query will return, which generic inputs (similar to function arguments) the query expects, and the search logic of our query. The :inputs keyword is used to describte the actual values that are given to the query as arguments. In the :rules part, customly made rules are defined. Rules are analogous to functions or routines in other languages; they are used when the same query logic needs to be used repeatedly. Furthermore, they allow to apply the same logic recursively, which is exactly what we will leverage. Finally, the :view keyword receives a function that describes how the information of the query is nicely formated for display.

Overall concept

The basic concept of the above query is similar to chapter 8 of the learndatalogtoday tutorial. Through the backlink property, all our journal pages are linked together in a sequential list. However, we are not interested in the endless sequential list, rather we are only interested in the latest uninterrupted sequence of journal pages where the habit has been ticked as done. We use a recursive rule that exactly finds all pages that belong to this uninterrupted sequence. Once we have them, we just need to count them to find the length of the current streak.

Start of :query

The :title part is self-explanatory, so let’s start directly with the beginning of the query part.

:query

[

:find (count ?p) (sum ?habit-today) ?habit-name (min ?date)

:keys count today habit lastdate

:in $ ?today [?habit ...] [[?habit2 ?habit-name]] %

The :find statement defines four bound variables ?p, ?habit-today, ?habit-name, and ?date. We are using three aggregate functions count, sum, and min. With the :keys statement, we can define names for the return values so that we can specifically select these values in the :view statement. Based on the :in statement, the query expects the following inputs. The $ describes the basic input of a database and is not interesting. Next, we have one input variable ?today with which we let the query know which date we have today. Next comes a collection of the habits that we want to track and a relation that is used to translate the queried habits into a displayable string. The % in the end of the line demarks the rules that are inputed.

The :where clause.

The :where clause is part of the :query and defines the highlevel logic of finding an uninterrupted sequence of days. Let us start with the first part of this clause.

:where

[(= ?habit ?habit2)]

[?p_today :block/journal-day ?today]

[?p_today :block/journal? true]

First, we require that the values of ?habit and ?habit2 are equal. Don’t bother if you do not understand this line yet. It will be covered in the explanation of the relation in the :in and :inputs statement. In the next two lines, the journal page of today’s date is bound to the variable ?p_today.

or-join to count different conditions

Next, we are going to use an or-join clause that allows us to count two different cases. Either, the habit is ticked as done today or not. If it is ticked as done today, we want to know the length of the current streak. If the habit was not yet done, we want to know when we last did that habit. This second question can equally be framed as searching an uninterrupted sequence of days where the habit was not done. We will employ a scheme that is also described in this stackoverflow answer. In the :find statement we used the aggregation (count ?p) which will give us the correct length of the positive and negative streaks. Therefore, we need to define a new variable that determines in which part of the or-join clause we counted; it determines whether we counted pages of a positive or negative streak. This new variable is ?habit-today and we saw it previously in the :find statement where we used the sum aggregation for it.

Before we jump into the specifics of the or-join clause, I want to mention two minor details. Recall, first, that those conditions within the or-join that need to be connected by and-logic need to go into an and clause. Second, the [?p ?p_today ?habit ?habit-today ?date] defines which variables within the or-join clause are bound to variables defined outside of the clause. All other variables within the or-join clause are not available outside of it.

Detecting a positive streak

(or-join [?p ?p_today ?habit ?habit-today ?date]

(and

(pages-next-day ?p ?p_today ?habit true ?date)

[(ground true) ?habit-today]

)

The first condition in the and clause is a customly defined rule. We will look at that rule in more detail later. For now it suffices to know, that the rule expects identifiers for two journal page entries, ?p and ?p_today. It checks, whether the two days are consecutive days, or linked to each other by other consecutive days based on the fact that the habit in question (defined by ?habit) is true on the two days and on all days in between. If that is true, then the habit was done today, and we set ?habit-today to true with the ground function. These two lines suffice to count the length of the current streak. The rest of the logic happens within the customly defined rule.

Let’s briefly discuss the five variables that go into the or-join clause, ?p, ?p_today, ?habit, ?habit-today, and ?date. In a way, ?p_today and ?habit have been set through the inputs of the query, they are already very specifically bound to values. ?p, ?habit-today, and ?date are different. They are also bound in :query as they are required in the :find clause. However, up to going into the or-join clause, they have not been specified in much more detail. As mentioned before, ?habit-today works as a variable that tells us whether we are in a positive or a negative streak. ?p will bind to all the days that belong to the current streak. ?date will contain the date information associated with these ?p.

Detecting a negative streak

(and

(pages-next-day ?p ?p_today ?habit false _)

[(ground false) ?habit-today]

[?p :block/journal-day ?date_]

[?p :block/original-name ?name]

[(vector ?date_ ?name) ?date]

)

)

]

The second and clause is for detecting a negative streak. It starts with the same customly defined rule as the first and clause. However, the fourth argument is false instead of true. Furthermore, we do ommit (_) the last variable that previously was bound to ?date. In the second line, we set ?habit-today to false to mark that we have found a negative streak. Beware, only the first line in one of the two and clauses will evaluate to true and, hence, only one of the lines with the ground statement will actually be executed. This is not due to the quality of the or-join or the and clauses. Rather, this is due to the logic of the data itself and the logic of the pages-next-day customly defined rule.

This clause has three more lines: these lines are used to extract the date information associated with the page ?p. Here, we use the vector statement to pack the ?date_ of type int and the nicely formatted name of the date ?name into one variable ?date. In the :find statement, we have the min aggregation for the ?date variable. By definition, datascript will return the tuple with minimal first entry. This is why we add the int type ?date_ to the tuple first.

With this, we are at the end of the :where statement. Before we draw our attention to the :rules part where the logic of the :where continues, let’s briefly look at the :inputs statement.

:inputs directive

The next line after the :where statement is the :input statement which is closely related to the :in statement. Both of them can be seen below.

:inputs [:today [:anki :sports] [[:anki "Anki"] [:sports "Sports"]] ]

:in $ ?today [?habit ...] [[?habit2 ?habit-name]] %

We use three different types of inputs: a simple input parameter, a collection, and a relation. For each of these input types there is a part in the :in statement and a corresponding part in the :inputs statement. While the :in statement defines the arguments that can be handed over to the query, the :inputs statement now hands over actual values for these arguments.

We have already learned previously that ?today is just a simple input parameter. It will be bound to a variable of type int that represents the current date. Fortunately, logseq provides us with a shortcut: logseq automatically translates the :today in the :input statement to this value.

Next comes the collection. It allows us to use the same :query for different habits. The :query expects one value that is bound to the variable ?habit and returns the correct information. With the syntax [?habit ...] in the :in statement we tell the query that it will receive multiple values for this variable. Furthermore, we tell it that it should run the query for each of these variables independently. You can think of it as looping or better as mapping a list of values to the same function and collecting all the outputs. [:anki :sports] in the :inputs statement instantiates now the exact values of that list (correct: collection). Unfortunately, :anki and :sports are not of a displayable type. They are neither strings nor integers. Actually, I do not know what type they are.

However, to use the information associated with either :anki or :sports, we use a relation to connect these variables of weird types to string variables. The relation is a list of tuples and can be regarded as a separate database that the query can use. We realize this additional information as [[:anki "Anki"] [:sports "Sports"]] in the inputs statement. In the :in statement, we tell the query that the first entry of the tuple should be bound to the ?habit2 variable and the second entry will be bound to the ?habit-name variable. In the very first line of the :where clause we have [(= ?habit ?habit2)]. Thereby, the variable ?habit from the collection gets connected to the ?habit-name variable of type string via the intermediate variable ?habit2. We require ?habit-name in the :find statement as part of the output. Were we to require ?habit in the :find statement, logseq would raise an error as logseq cannot display the value behind ?habit due to its weird type.

After we have discussed the complicated topic of :inputs, :in, collections, and relations, let’s continue with the logic of our query and discuss the :rules statement.

Our customly defined rules

Helper rules

Before we look at the recursively defined rule—the core of the query—we will briefly discuss some helper “functions”.

:rules [

;; similar to predefined property rule

[(test-property ?b ?type ?testval)

[?b :block/properties ?props]

[(get ?props ?type) ?val]

[(== ?val ?testval)]

]

;; check whether specific habit was done in tracker block

[(habit-block ?b ?habit ?val)

[test-property ?b :type "tracker"]

[test-property ?b ?habit ?val]

]

The test-property rule is very similar to the predefined property rule. However, the predefind property rule is not available within the :rules statement; it seems to be only available within the :where clause. Nevertheless, let’s discuss. test-property expects three variables ?b, ?type, and ?testval. In the first line of the rule body, we introduce a new variable ?props and bind it to the block properties of ?b. Therefore, ?b is a variable for a block. ?props is a map that contains keys and associated values which can be retrieved with the get function. In the next line, we retrieve the value from ?props that is given by ?type and bind it to the new variable ?val. Finally, the rule tests whether the values of ?val and ?testval are similar. In conclusion, test-property expects a block reference in ?p and evaluates to true only if there is a property within that block with the name given by ?type and if that property has the same value as given by ?testval.

The next helper rule takes advantage of the previously defined rule. habit-block first tests whether a given block ?b is a block that is used for tracking habits. Next, the rule checks whether the ?habit in question has the value given by ?val.

Given these helper rules, we can now face the recursive pages-next-day rule.

The recursive rule

In datalog / datascript a recursive rule is defined by writing down the same rule head at least twice with different rule bodies for each head. Let`s first focus on the first rule definition.

[(pages-next-day ?p1 ?p2 ?habit ?val ?date)

;; fastest when we begin search at the known page ?p2

[?b2 :block/page ?p2]

(habit-block ?b2 ?habit ?val)

[?b2 :block/refs ?p1]

[?p1 :block/journal? true]

[?p2 :block/journal-day ?date2]

[?p2 :block/original-name ?name2]

[(vector ?date2 ?name2) ?date]

]

This rule requires two variables representing pages, ?p1 and ?p2. We want this specific definition of the rule to evaluate to true only if ?p1 is the journal page directly before the journal page ?p2 and if on the day of ?p2 the ?habit in question was either true or false depending on ?val. According to the logic of the above :where clause, we can assume that ?p2 was already checked as being a journal page. With the first two lines in the rule, we extract the block ?b2 in page ?p2 that is used as habit tracking block. Within habit-block we also test whether our ?habit in question is set as we want. If that is not true, the rule evaluates to false and returns… If such a ?b2 can be found, we know that it has exactly one reference in it and this reference points to the previous day. Hence, the third line. In line four, testing for ?p1 being a journal page might not be necessary, but we do it anyways. The last three lines of the definition extract the date information associated with ?p2 and save it into the tuple ?date as we have seen before. If you’ve come so far, understanding the second definition of this rule will be a piece of cake.

But first, let’s think about what the rule can do so far: it can tell us whether to pages are “directly consecutive” and whether the habit was done on the younger of these two days. If ?p1 and ?p2 are separated by an intermediate day, on which the habit was also done, the current definition of the rule will fail. We will use the notion of an intermediate day in the second definition of the rule:

[(pages-next-day ?p1 ?p2 ?habit ?val ?date)

;; fastest when we begin search at the known page ?p2

[?b2 :block/page ?p2]

(habit-block ?b2 ?habit ?val)

;; ?px is the page that ?p2 links to.

;; Is it connected to ?p1? If yes, then ?p1 and ?p2 are also connected.

[?b2 :block/refs ?px]

[?px :block/journal? true]

(pages-next-day ?p1 ?px ?habit ?val ?date)

]

The first two lines of the second definition are exactly the same as before. This is a common theme for recursicely defined rules. But now we introduce the mysterious intermediate day ?px. By the definition of our data scheme (the backlink property), we know that ?px is the direct predecessor of ?p2. Now instead of finding out whether ?p1 and ?p2 are connected, we only need to find out whether ?p1 and ?px are connected. And as the rule definition is recursive, we will find a definite answer sometime.

There is one subtlety in the last line: given that in the first definition ?date was associated to ?p2, in the second definition, ?date is associated to ?px. In other words, by recursive execution, ?date will always be associated to the date of the day after ?p1. However, for the day ?p1 we never test if the habit was done. Hence, ?date is associated to alle the days the habit was done. This suffices if we want to know the start of a positive streak. In case of a negative streak, however, we would like to know the day before that streak started as, after all, that is the day the previous positive streak ended. That is why we extract different ?date variables in the two and clauses above.

Best practices for efficiency in recursive rules

I tried to follow these principles:

- Put the most selective clause first in query

- Join along

- Develop more selective clauses from where you come from.

It is rather easy to find the journal page of ?today which is bound to the variable ?p_today. In :where, we then insert ?p_today at the second position of our rule. The rule is only checking the blocks within this one page, and then extracts only one new page from it—the previous day to which the backlink property points to. In my opinion, this is the most efficient way to write this task into a recursive rule. Consider this bad practice example of the first definition of our recursive rule:

;; do not use. Is very slow.

[(pages-next-day ?p1 ?p2 ?habit ?val ?date)

;; test whether ?p1 is a journal page

[?p1 :block/journal? true]

;; find all the blocks that reference ?p1

[?b2 :block/refs ?p1]

;; which of these blocks is a tracking block

(habit-block ?b2 ?habit ?val)

;; and does this tracking block actually belong to ?p2

[?b2 :block/page ?p2]

[?p2 :block/journal-day ?date2]

[?p2 :block/original-name ?name2]

[(vector ?date2 ?name2) ?date]]

]

If you check closely, the lines have just been swaped. Nevertheless, this implementatino has terrible performance. Instead of continuing our search from ?p2 which we know something about, we bind ?p1 to all possible journal pages. Then we bind ?b2 to all possible blocks that reference all these ?p1. Only then, we start to prune our list of possible ?p1 and ?b2.

As we’ve now understood the hardest part of the query, let’s take a look on how to display the outputs nicely in table format.

Formatting with :view

Our query will return a list of results. The length of that list and its contents are shaped by the very beginning of the :query statement:

:find (count ?p) (sum ?habit-today) ?habit-name (min ?date)

:keys count today habit lastdate

:in $ ?today [?habit ...] [[?habit2 ?habit-name]] %

Given the aggregation functions in the :find statement, we will get one result per ?habit-name. With the :keys statement, we require the query to return a map (similar to dictionaries in Python). Hence, we have a list of maps as output of the query. We format it with these lines of code.

:view (fn [rows] [:table

[:thead

[:tr

[:th "Habit"]

[:th "Current streak"]

[:th "Start of current streak / End of last streak"]]]

[:tbody

(for [ r rows] [:tr

[:td (get r :habit)]

[:td (if (> (int (get r :today)) 0)

(+ "✔️ - " (get r :count) (if (> (int (get r :count)) 1) " days" " day"))

"❌")

]

[:td

[:a

{:href

(str "#/page/" (nth (get r :lastdate) 1))

} (nth (get r :lastdate) 1)

]

]

])

]

])

The :view keyword requires the definition of a function which we start with the opening round bracket ( and the fn keyword. This function expects a list, that we bind to the variable rows within the function. Then, we use Clojure’s hiccup to open a [:table. Beware, that this table is closed by a square bracket ] only later. Similarly, we define the table head and then the table body. After opening the table body, we start a for loop, that iterates over rows and puts its list elements into the variable r. Recall, r is a map (dictionary). Within the loop, we open for each r a html row with the hiccup [:tr that obviously needs to be closed again within the loop. The first column of the table should give the name of the habit. We retrieve it with (get r :habit) where :habit is the key to the actual habit name, as was defined in the :keys statement. Next comes an if statement differentiating between positive and negative streaks as :today points to the result of (sum ?habit-today). In case of a positive habit, we have another if statement to distinguish between one day and several days. As in both if statements we want to compare integers, we have to convert the results to integers with the int function. In the third column we create a link to the page being either the start of a positive streak or, in case of a negative streak, the end of the previous positive streak. The function str concatenates several strings to one long string. The only new thing here is the use of nth to unpack the values of the :lastdate / ?date tuple.

Your homework

Easy: define a new custom rule

You might have noticed that the first three lines of the two definitions of the pages-next-day rule are similar. In such cases it is always advisable to reduce similar logic into a separate rule: Rewrite these rules by introducing a new rule get-backlink-page.

Click to see a possible solution!

[(get-backlink-page ?p1 ?p2 ?habit ?val)

[?b2 :block/page ?p2]

(habit-block ?b2 ?habit ?val)

[?b2 :block/refs ?p1]

[?p1 :block/journal? true]

]

[(pages-next-day ?p1 ?p2 ?habit ?val ?date)

(get-backlink-page ?p1 ?p2 ?habit ?val)

[?p2 :block/journal-day ?date2]

[?p2 :block/original-name ?name2]

[(vector ?date2 ?name2) ?date]

]

[(pages-next-day ?p1 ?p2 ?habit ?val ?date)

;; ?px is the page that ?p2 links to.

(get-backlink-page ?px ?p2 ?habit ?val)

(pages-next-day ?p1 ?px ?habit ?val ?date)

]Easy: Caching and debugging

Once your habits extend to 30+ days you might see that this query still takes up to 10 seconds to execute. I would love to add some caching to the query, but such optionality does not yet exist. Furthermore, I would like to debug the runtimes of different queries to further speed up the query. However, I have not yet investigated on how to do proper debugging with these advanced queries.

Advanced

If a habit was not yet done today, the only information being displayed is when the habit was done last. Can you script a query that distinguishes between a habit that was last done yesterday (a streak that has to be continued today) and a habit that you stopped doing long ago (you will not lose a currently runnning streak if you miss this habit today). For an illustration of the problem consider the following table.

![]()

This table shows that the Anki habit was done today (49 days streak). The Duolingo habit was not done yet, but up to yesterday it was done—up to yesterday the streak was 48 days. The meditation habit was not done today, nor yesterday. Here are some tips on how to accomplish that task:

- Use

:yesterdayin the:inputs. You also need to add another input variable in:in. - Use another

andin theor-jointo determine the length of a positive streak that would start from yesterday in to the past. Most likely, you will need to add another variable in:find. - Within

:viewintroduce some moreifstatements for formatting the new information

Click to see a possible solution!

{

:title [:h1 "My current streaks"]

:query

[

:find (count ?p) (sum ?habit-today) (sum ?habit-yesterday) ?habit-name (min ?date)

:keys count today yesterday habit lastdate

:in $ ?today ?yesterday [?habit ...] [[?habit2 ?habit-name]] %

:where

[(= ?habit ?habit2)]

[?p_today :block/journal-day ?today]

[?p_today :block/journal? true]

[?p_yesterday :block/journal-day ?yesterday]

[?p_yesterday :block/journal? true]

(or-join [?p ?p_today ?p_yesterday ?habit ?habit-today ?habit-yesterday ?date]

(and

(pages-next-day ?p ?p_today ?habit true ?date)

[(ground true) ?habit-today]

[(ground false) ?habit-yesterday]

)

(and

(habit-not-page ?p_today ?habit)

(pages-next-day ?p ?p_yesterday ?habit true ?date)

[(ground false) ?habit-today]

[(ground true) ?habit-yesterday]

)

(and

(habit-not-page ?p_today ?habit)

(pages-next-day ?p ?p_yesterday ?habit false _)

[(ground false) ?habit-today]

[(ground false) ?habit-yesterday]

[?p :block/journal-day ?date_]

[?p :block/original-name ?name]

[(vector ?date_ ?name) ?date]

)

)

]

:inputs [:today :yesterday [:anki :duolingo :meditation] [[:anki "Anki"] [:duolingo "Duolingo"] [:meditation "Meditation"]] ]

:rules [

;; similar to predefined property rule

[(test-property ?b ?type ?testval)

[?b :block/properties ?props]

[(get ?props ?type) ?val]

[(== ?val ?testval)]

]

;; check whether specific habit was done in tracker block

[(habit-block ?b ?habit ?val)

[test-property ?b :type "tracker"]

[test-property ?b ?habit ?val]

]

[(habit-not-page ?p ?habit)

[?b :block/page ?p]

(habit-block ?b ?habit false)

]

[(get-backlink-page ?p1 ?p2 ?habit ?val)

[?b2 :block/page ?p2]

(habit-block ?b2 ?habit ?val)

[?b2 :block/refs ?p1]

[?p1 :block/journal? true]

]

[(pages-next-day ?p1 ?p2 ?habit ?val ?date)

(get-backlink-page ?p1 ?p2 ?habit ?val)

[?p2 :block/journal-day ?date2]

[?p2 :block/original-name ?name2]

[(vector ?date2 ?name2) ?date]

]

[(pages-next-day ?p1 ?p2 ?habit ?val ?date)

;; ?px is the page that ?p2 links to.

(get-backlink-page ?px ?p2 ?habit ?val)

(pages-next-day ?p1 ?px ?habit ?val ?date)

]

]

:view (fn [rows] [:table

[:thead

[:tr

[:th "Habit"]

[:th "Current streak"]

[:th "Start of current streak / End of last streak"]]]

[:tbody

(for [ r rows] [:tr

[:td (get r :habit)]

[:td (if (> (int (get r :today)) 0)

(+ "✔️ - " (get r :count) (if (> (int (get r :count)) 1) " days" " day"))

(if (> (int (get r :yesterday)) 0)

(+ "❌ - " (get r :count) (if (> (int (get r :count)) 1) " days" " day"))

"❌ ❌ ❌"

)

)]

[:td

[:a

{:href

(str "#/page/" (nth (get r :lastdate) 1))

} (nth (get r :lastdate) 1)

]

]

])

]

])

}Hard to impossible

Do you think you can modify the query to encompass different frequencies for the habits? Say one habit needs to be done daily, but another one only needs to be done weekly. I guess datascript could in principle be used for that, but the logic becomes increasingly complicated.

With this, we are at the end of the tutorial. I hope you’re ready to use this advanced query to track your own habits or to create your own advanced queries with all the possibilites given by logseq. If you find bugs or have suggestions, feel free to file an issue. In case you have broader questions, try the logseq forum.